Key Driving Forces of Social Innovation: Impact Investment and Social Enterprise

December 21, 2018 - By Heather Grady

Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors and the China Global Philanthropy Institute recently held a launch for a book authored by Vice President Heather Grady titled Key Driving Forces of Social Innovation, focused on encouraging the nascent impact investing and social enterprise sector in China. The following article is adapted from her talking points at the book release event on December 11, 2018 in Shenzhen. The book is currently available in Mandarin; for more information, email [email protected].

The philanthropy sector around the world is exploring how to become more sustainable, in both impact and financial terms. My new book, Key Driving Forces of Social Innovation, represents a small contribution to that effort. It drew on substantial interviews with more than thirty experts, and has been written primarily for a Chinese audience, though we believe its key concepts and case studies will be of interest to philanthropists and foundation colleagues anywhere.

In China, as in every country, governments hold fundamental responsibilities for ensuring that all people are educated and healthy, and have opportunities to be productive and prosperous. The field of philanthropy in China is growing, so there as elsewhere, philanthropy and impact investment are finding their roles complementary to—not replacing—the fundamental role and responsibility of the public sector. Indeed, today in China as elsewhere, smart combinations of public and private funding will be an essential component in tackling complex social and environmental challenges.

How Impact Investing Contributes to this Shared Responsibility

In a book that Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors published more than a decade ago, Solutions for Impact Investors: From Strategy to Implementation, we wrote that “impact investing can create social good at scale and begin to address some of the world’s most pressing problems where commercial markets and donor-based programs have not.”

Philanthropists who have been giving away funds through operational programs or grants can add impact investing to their toolbox, and this presents a tremendous opportunity for foundations to put more of their assets to work to create greater impact. A point raised in our book launch discussion in China mirrors that in other contexts: that there will always be program areas and goals that require grants rather than investments for financial return. So the starting point for Chinese investors is to be sure that they are selecting a tool that matches the problem. Moreover, many social enterprises can make good use of grants, and most not-for-profits use grant funds before they create something investible for their revenue streams. But where philanthropists and foundations have objectives that lend themselves to impact investing resources, they should see how this can reinforce and support those objectives in addition to their current portfolio. Crucial to progress is a frank examination of lessons learned, exchange across countries and sectors, and developing and testing successful models.

Key Concepts in Impact Investing and Social Enterprise

This volume for Chinese readers stressed that even when impact investors support social services, if the client of those programs is the government and the government is eventually paying for those services, then impact investors are the financiers, not the donors. They are making a fixed-term investment and aim to be repaid with interest (in the case of debt) or profit (in the case of equity). And it is particularly useful in certain cases: in piloting new approaches on which governments cannot afford to take a risk, or in funding social services or social enterprises in a start-up phase where there are potential efficiency or productivity gains to be realized over time.

The Global Impact Investment Network (GIIN) provides a wealth of information and guidance for both new entrants to the field and experienced practitioners. Concepts like intentionality, and approaches to impact measurement, will be important for Chinese impact investors to learn and use. A hallmark of impact investing is the commitment of the investor to measure and report the social and environmental performance and progress of underlying investments. In new markets like China, impact measurement helps ensure transparency and accountability, and is essential to informing the practice of impact investing and building the field.

Our discussion at the book launch raised the question of asset classes. Whereas some of this field’s leaders have earlier written that impact investments will constitute one standalone asset class, we clarified that impact investments can be made across asset classes, including but not limited to cash equivalents, fixed income, venture capital and private equity. Impact investors can also earn fees by providing catalytic instruments such as guarantees. In China as elsewhere, investors’ return expectations and the instruments in which they invest will reflect their intent and are typically driven by the economics of the investment. Some will support higher risk early-stage social enterprises in challenging rural markets, though most will likely look to finance the expansion of proven business models to reach scale, in the expectation of market or near market rate returns.

Clarifying how Change will Happen

Impact investors, like philanthropists, will need to think about how they believe change will happen—a theory of change leading them to make an informed choice. We make assumptions with these investments just as we make assumptions when we decide which traditional businesses to invest in to make a good financial return, or how to give away our charitable money. These assumptions must be tested over time through monitoring and evaluation, itself a growing field in China.

While Chinese audiences are curious about terms like Program Related Investments and Mission Related Investments known and used by many U.S. foundations, their entirely different legal framework means they will create their own nomenclature and practices. What will be similar is that below-market mission investments will increasingly be made across asset classes, in the form of loans, loan guarantees, cash deposits, equity investments, and other investments made for specific purposes, like elderly care and workforce development.

Social Impact Bonds, or Pay for Success models, are being actively explored in China, with the city of Shenzhen aiming to be a locus of experimentation on these instruments and social finance more broadly. Sections of the book devoted to this topic, including famous case studies form the U.S. and UK, should help expand the important exchange of lessons learned across national boundaries on this effort-intensive tool.

Getting Started in Impact Investing

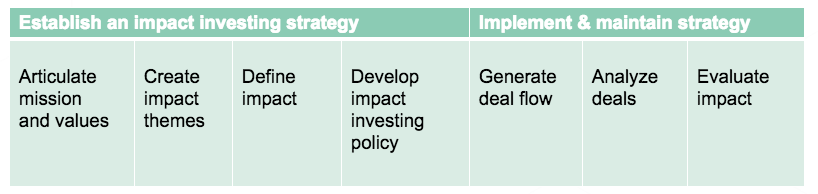

RPA’s impact investing workshops in China have emphasized the importance of preparation. Our early volume on impact investing listed seven steps in the cycle that illustrate the investor preparation and reflection needed before a deal flow is even generated:

Given the complexity of this endeavor, philanthropists, foundations, and new investors will need to educate not only themselves, but their board, staff, and investment committees. This can be helped along by providing examples of investments and what they should be looking for in investees, helping them identify whether they want to invest in funds or direct investments, and creating user-friendly tools in-house to do this, or finding and using external asset managers. Risks can be mitigated through the way investments are structured or management assistance. In China as elsewhere, some investees are more impact investment ready than others, a reality for which impact investors should simply plan.

Case Studies and Examples of Impact Investing and Social Enterprise in the U.S. and China

The book concludes with several notable examples from the field of impact investment and social finance in the U.S. and China. The world’s most famous foundation is always a topic of interest in China, so a section describes how the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation launched PRIs in its program areas of education, international development, and global health. A second example is Morgan Stanley’s Institute for Sustainable Investing. Case studies on social enterprises and social impact bonds in education in the U.S. offer in-depth illustrations of the opportunities and challenges. Chinese case studies written by the Social Finance and Innovation Center of the China Global Philanthropy Institute focus on Dao Ventures, Tsing Capital, and the Aiyou Foundation. But whether examining the U.S. or China, the field is moving fast and there are a growing number of examples to learn from.

As the many examples and case studies in this book show, important factors for success are collaboration, patience, and communication. These are social endeavors that build on processes of listening, discovery, experimentation, sometimes failure, and integrating new knowledge of what works and what does not. China’s place in this landscape of philanthropy and impact investing is important, and rapidly evolving. Philanthropy and impact investing that crosses borders helps to increase the mobility of ideas and greater understanding between different cultures. We hope this book makes a contribution to that in the years to come.

****

More about Impact Investment and Social Enterprise: Key Driving Forces of Social Innovation:

This book captures years of personal experience in philanthropy as well as insights gained from well over thirty experts interviewed. The book discusses:

- Partnerships between philanthropy and government;

- The five steps in the Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors Philanthropy Roadmap;

- Key philanthropy concepts;

- How to manage impact investing, particularly for organizations and individuals who have been generously giving away funds; and

- How to predict, measure and evaluate impact.

We also include case studies to further illustrate the concepts. For more information, please email [email protected].

Heather Grady is a Vice President in RPA’s San Francisco office and leads the organization’s strategy and program development in global philanthropy, including collaboratives, global programs, research, and publications. She also serves as an Adjunct Professor for the Executive Management in Philanthropy Program at the China Global Philanthropy Institute.

Back to News