Philanthropy Framework Profile: The Wallace Foundation

December 14, 2018Key Statistics

Founding Date: Earliest predecessor fund founded 1965

Location: New York City

Assets (2015): $1.45 billion

Total Grantmaking (2015): $69.5 million

Number of staff: 52

Background

The Wallace Foundation seeks to expand learning and enrichment for disadvantaged children and the vitality of the arts for everyone. Based in New York City, the Foundation traces its roots back more than half a century to the generosity of DeWitt and Lila Acheson Wallace, founders of The Reader’s Digest Association. Incorporating multiple trusts from the Wallace estate in 1986, the Foundation took on its current consolidated structure as an independent private foundation in 2003.

Core Framework

“We have many of the attributes of a traditional foundation, with the ability to invest in grantees’ efforts to test out possible solutions to significant problems. At the same time, we share some attributes of a think tank–the commitment to gathering and using credible evidence with the goal of informing policy and practice so that we’re also, in a sense, setting up R&D efforts with our grantee partners. So it’s a combination think tank and more traditional foundation.”

– Lucas Held, Director of Communications

The Wallace Foundation operates as a connected foundation. It demonstrates its social compact through three integrated core activities or disciplines (program, research, and communications) and holds itself accountable first to its board, then the general public. In terms of operating capabilities, it is most influenced by centralized, interdisciplinary decision-making while thoughtfully balancing a buying and building resource model.

As a combination think-tank and traditional foundation, a fitting analogy for the Wallace Foundation’s approach is that of a medical professional with both an MD and a PhD. The rigorous lab work informs patient care, while the clinical work informs the pursuit of additional knowledge. This carefully curated identity has led to the Foundation’s success and growth over the years.

“The charter created when our predecessor funds were merged includes youth development, the arts, national parks, historic preservation, libraries, and everything else the Wallaces were interested in … [yet] … the board is completely free to set the mission of the organization however they wish.”

– Will Miller, President

Charter

The Wallace Foundation operates based on a connected style of charter, where the vision, preferences, and approach of DeWitt and Lila Acheson Wallace guide and inform but do not tightly constrain current decision making.

During their lives, DeWitt and Lila Acheson Wallace generously gave to a wide range of causes – from historic preservation to youth development. Upon their deaths in the 1980s, they left the majority of their estate in the form of multiple charitable trusts. In 2003, the remaining separate giving vehicles were merged into a single entity, The Wallace Foundation, with the formal charter including goals of each trust along with a catch-all that includes “anything else for the good of mankind.” This allows complete freedom, although current trustee and staff leaders are greatly influenced by the founders’ philanthropic goals.

For example, from 2003 to 2009 the Foundation narrowed its programmatic priorities and mission until it had an exclusive focus on “learning and enrichment for the least advantaged children.” This honored DeWitt Wallace’s life-long interest in youth development and focused the grantmaking activity to a narrow, manageable goal. In 2012, becoming increasingly aware of the lack of focus in the arts, the Board decided to add back the support of nonprofit arts organizations to honor Lila Wallace’s life-long interest in the arts and her stated belief that the “arts belong to everyone.” This turning point made clear the “connected” nature of the foundation’s charter, since Lila’s interest in the arts pushed the board to make the shift despite no mandate requiring it to do so. The Wallace Foundation’s mission statement today is “to expand learning and enrichment for disadvantaged children and the vitality of the arts for everyone.” This charter has also shaped the foundation’s Statement of Core Values and its articulation of The Wallace Approach.

The Statement of Core Values

“At The Wallace Foundation, we seek to improve complex social systems in ways that are meaningful, measureable, and sustainable. We value behavior that demonstrates a commitment to mutual respect and support, diversity, continuous learning, collaboration, excellence, and accountability.”

The Wallace Approach

“Our approach to accomplishing our mission emerges from the idea that foundations have a unique but often untapped capacity to develop evidence and experiences that can help advance an entire field. …By developing ideas and information to advance education, the arts and learning and enrichment for young people, we can stretch our philanthropic dollar, giving our work far greater impact than the sum of our individual grants. Our efforts, then, seek not only to help our individual grant recipients but also to develop credible knowledge useful to many others.”

Social Compact

“We review items to be posted on our website for credibility, for clarity, for organization, and for nonpartisanship … in order to maintain our reputation for credibility, which is essential to having impact through knowledge.”

– Lucas Held, Director of Communications

The Foundation feels most accountable to its board, then also to the general public. Research, grantmaking, and communications comprise its core activities towards maximizing net social value. The Foundation pursues the above-mentioned activities by engaging grantees, beneficiaries, policymakers, direct service providers, and peer funders—all while broadly sharing best practices to have the widest impact possible.

The core activities mentioned take multiple forms, including direct grants, technical assistance, peer learning communities and convenings. The interaction with grantees takes on a “co-creation” lens, where the Foundation and the grantee are partners in both gathering information to understand needs and deploying resources to address those needs. When assessing the success of a grant for example, the Foundation asks and factors in what the grantee measures.

The Foundation also carefully engages in policy analysis and seeks to contribute to policy change in cases where it judges the evidence it has gathered to be sufficiently strong and where the risk of unintentional harm is sufficiently low. Regarding communications, the Foundation is committed to, values, and pursues transparency in sharing its approach and funding priorities. In sharing its research and learnings, the Foundation’s communication efforts focus on informing policymakers, intermediaries, and direct service providers involved in their three target issue areas. This broad dissemination of best practices allows the Foundation to steward its limited resources to have widespread effect, well beyond what grants alone could accomplish.

Operating Capabilities

“This idea of bringing the three areas of Communications, Research and Program Area together was really compelling and intriguing.”

– Nancy Devine, former Director of Learning & Enrichment (Program)

The Wallace Foundation’s core capabilities are grounded in an approach that values collaborative, interdisciplinary decision making, balancing both a building and buying approach to dispersing resources, an independent style of internal peer relationships, a creative approach to strategy development, and a deep program focus with a proactive approach to grantmaking decisions.

The Foundation’s approach to decision making is central to its identity and culture. High-level decisions are centralized at the board level while programmatic decisions progress through an interdisciplinary process with final board approval. This process for field-facing decisions is driven by interdisciplinary teams consisting of representatives from the Foundation’s three units: program, research, and communications.

The Foundation’s approach to resourcing work strikes a balance between both buying and building. This is most clearly seen through its “building” applied research capabilities by hiring five PhD Research and Evaluation experts, and its “buying” direct service through grants and contracts which are targeted to go 75% to 80% to support programmatic work in the field, 10% to 12% to conduct research and evaluation of those activities, and 8% to 10% for communications activities to disseminate the knowledge gained. The Foundation builds its own internal staff in the three field-facing disciplines mentioned above (program, research, and communications) and three internal-facing operating disciplines (investments, finance, administrative services), supplemented by selectively outsourcing certain discrete functions – including technical assistance for grantees and consultants for operations and marketing. As a non-operating foundation, the Foundation also “buys” the direct service through engaged grantmaking rather than executing the service themselves.

The combination of each core capability leads to a nuanced, thoughtful approach to strategy. Will Miller describes how this has been applied to the allocation of resources across program areas: “When I got here, I said, ’So, how do you decide how much to spend in each area?’ My predecessor [Christine DeVita] said, ‘The quality of the ideas. I don’t believe in budgets.’ I thought that was really smart and I seized on that.”

Theory of the Foundation in Action

The program folks, before they have any idea what the initiative’s going to look like, are in a room with the research and evaluation folks and the communications folks asking these questions, gathering information together, talking about what options to suggest.”

– Edward Pauly, Director of Research

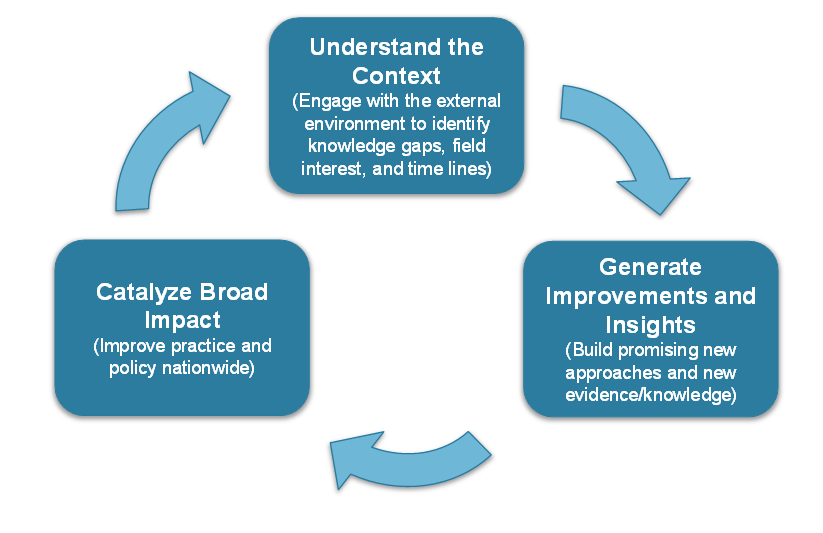

As discussed above, the Foundation intentionally pursues an interdisciplinary, collaborative approach to program decisions with no set budget for any one program area. In selecting grantees, members of each of three units (program, research, and communications) gather together to make decisions based on programmatic priorities. This model contrasts with the more commonly-used approach in most foundations, where each unit focuses on its area of expertise with limited direct input from other units. For Wallace, as each unit brings their particular lens to the table in an interdisciplinary team, the result is a culture of collaboration and continuous improvement towards its theory of change:

The Wallace Foundation Internal Theory of Change

The approach begins by exploring the context to identify an unanswered question that, if answered, could help propel progress in a field. The foundation then works with a small number of grantees whom it funds to test out new approaches that create benefits locally, and independent researchers who work to understand what works, what doesn’t, and why. Those insights are the basis for communications to the field with the goal of improving practice and policy nationally. Benefits of this approach include perspective, depth, and mutual benefit. Each unit must consider two other lenses before moving forward, which builds buy-in and trust between the three teams. The resulting knowledge sharing leads to deeply informed units as they each approach their work. In this way the program unit makes informed grants, the communications unit delivers nuanced communications, and the research team pursues practical analysis. In the interdisciplinary team, each idea is challenged from a host of observers, so it has a better chance of success.

Each specific discipline benefits from the two others. From the program perspective, deep issue research and broad potential messaging informs grantmaking decisions. From the communications perspective, the research unit brings a high level of rigor to the evidence that is the basis of engaging leading service providers and policymakers while program staff inform the best messaging for practitioners. From the research perspective, the other two units bring different networks to bear on which study should be pursued and what questions should be answered.

This approach does not come without costs. The timeline of each decision is quite long compared to grantmaking by more autonomous program teams. Significant resources are also expended to convene these interdisciplinary teams and arrive at consensus. Potential frustration across units can drag on morale and productivity by requiring buy-in from other teams, while—for certain decisions—that unit might think itself more qualified to decide. As former program director Nancy Devine summarized: “I think this theory of change really works, [but] it’s just not easy.”

This approach is highlighted in the Foundation’s Partnerships for Social and Emotional Learning Initiative, which selected and funded a cohort of six communities to understand how schools and afterschool programs could work together to help students acquire skills like persistence and teamwork. Each of the three units, driven by different yet important motivations, gave their perspective: program staff preferred cities with the greatest need, evaluation staff wanted to optimize for learning potential, and communications staff looked for opportunities to package the results to different audiences. If one unit were in charge, the six cities would have been skewed to their preference. However, since each of these perspectives were challenged by the other units, the ultimate cities selected were well-rounded with elements of each unit’s considerations. The same interdisciplinary decision making – informed by discussions with grantees – will be applied to all important decisions. With luck, and adjustments to inevitable stumbles, at the end of six years the six communities will have helped thousands of children directly, and, the field will know more about the opportunities – and challenges – of using the combined power of school and afterschool to help equip young people for success.

“One of the unusual aspects of our approach to interdisciplinary teams is we don’t have the program people decide this and then the R&E people decide that and then the communications people decide this. All three are involved in the design of the entire initiative including what’s the question that we should be tackling. That makes it impactful, and rich … and difficult.”

– Will Miller, President

Back to News